The Dawes Act of 1887

If centuries of disease, warfare, famine and disruption of their traditional societies and ways of life weren't enough injustice for Natives to suffer, the Dawes Act of 1887 and related legislation added to the misery. The Dawes Act, also known as the Dawes Severalty Act or the General Allotment Act of 1887, was an act passed by Congress to reduce the amount of lands given to Natives through reservation treaties by providing each family a homestead allotment of 160 acres and full citizenship. Or, that was how it was supposed to work.

In the later half of the 19th century, Settlers had spread across the American west and land was becoming scarce. Congressional policy makers began to look toward Native land to make up the shortfall. White Settlers in Oklahoma were anxious to bring it into the Union as a state, which meant shedding the Indian Territory designation. That was easier said than done. For decades the federal government had signed various treaties consigning tribes to land in Oklahoma. These treaties not only provided Natives with land held by the tribe, but also promised monetary annuities, food rations, services such as schooling, and the right of self government. In reality, few of these benefits actually happened. It fell to Indian Agents and government contractors to provide rations and administer each reservation, leading to widespread graft and corruption. There was also a sense that Natives needed to shed the last vestments of their old way of life and assimilate fully as American citizens. Indian boarding schools such as that at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, begun in 1879, had the same mission, destruction of Native-ness in favor of White-ness. The long title of the Dawes Act calls it, "an act for the allotment of lands in severalty to Indians on the various reservations, and to extend the protections of the laws of the United States and Territories over the Indians." Read, land grab and forcible assimilation.

Government employees began inventorying Native land and listing tribal members on Dawes Rolls in preparation for the allotments. Native leaders saw through the ruse and protested to Congress and through the courts. Not only would the act destroy any vestiges of traditional tribal self-government, but also communal ideas of land ownership and familial inheritance. Not dissuaded in the least, Congress passed the law in 1887,allotting each Native family 160 acres of land. Not only were the Five Southeastern Tribes in Oklahoma affected, so were other Natives in Oklahoma and Kansas, and throughout the West. The Curtis Act extended specifically to the Five Tribes of the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Cherokee, Creek/Muscogee and Seminole, through similar provisions. They would lose a combined 90 million acres in Oklahoma alone.

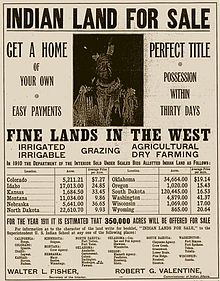

Chaos ensued. After the Natives had received their allotment of land, vast swaths of former reservation land were open for settlement. The government offered this land on the cheap to homesteaders who could prove it up. In Oklahoma, tribes had often had problems with White squatters known as Boomers, people who trespassed and set up farms on Native land and had to be forcibly removed by the Army. As rumors of impending land sales picked up, Sooners, or people who moved into Oklahoma sooner than the announced sale date were also a nuisance. Oklahoma experienced several land rushes, where Settlers would wait at the border of land intended for sale and rushed to claim the choicest parcels. The most famous was the Land Run of 1889, giving rise to the term 89'er, for people who had claimed land at that time, mostly land belonging to the Five Tribes. Another land run in 1891 opened Iowa, Sac and Fox, Potawatomi and Shawnee land. In 1892, Cheyenne and Arapahoe land was for sale. Then in 1893, land in the Cherokee Strip area of Oklahoma was sold. Then in 1895, Kickapoo land went the same way.

As White homesteaders rushed into the vacated lands, they ran into Sooners and Boomers who had settled their first and weren't about to go easily. Unscrupulous speculators also entered the act, buying land from Natives who weren't intending to prove up or farm their land, and would rather live as they always had, with relatives on their land. Many Natives had become used to reservation rationing. Without the seed, implements or knowledge of farming, and no game to hunt, many families found 160 acres of farmland to be completely useless anyway. Tribes who practiced communal ownership, or had a formerly nomadic lifestyle were totally unprepared for life as homesteaders and farmers, though many tried their best including Geronimo of the Apache. By 1900, tribes had lost over 2/3 of their original land, all self-government, and much of their traditional leadership and methods of kinship and property inheritance. To make matters worse, Congress did not extend citizenship to Natives until 1924, legal rights such as voting, suing in court and other means of protecting their rights were non-existent.

The downward spiral continued, Natives who lived in Oklahoma were affected by the Dust Bowl of the 1920's and the Depression of the 1930's. The Roosevelt Administration passed the Indian Reorganization Act, known as the Wheeler-Howard Law of 1934. This Act ended allotment, allowed tribes to organize their own self-government, apply for federal recognition and receive rights to tribal land which could not be sold to non-tribal members. It would take some tribes years to complete the process of achieving federal recognition, something many groups are still trying to achieve.

In the later half of the 19th century, Settlers had spread across the American west and land was becoming scarce. Congressional policy makers began to look toward Native land to make up the shortfall. White Settlers in Oklahoma were anxious to bring it into the Union as a state, which meant shedding the Indian Territory designation. That was easier said than done. For decades the federal government had signed various treaties consigning tribes to land in Oklahoma. These treaties not only provided Natives with land held by the tribe, but also promised monetary annuities, food rations, services such as schooling, and the right of self government. In reality, few of these benefits actually happened. It fell to Indian Agents and government contractors to provide rations and administer each reservation, leading to widespread graft and corruption. There was also a sense that Natives needed to shed the last vestments of their old way of life and assimilate fully as American citizens. Indian boarding schools such as that at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, begun in 1879, had the same mission, destruction of Native-ness in favor of White-ness. The long title of the Dawes Act calls it, "an act for the allotment of lands in severalty to Indians on the various reservations, and to extend the protections of the laws of the United States and Territories over the Indians." Read, land grab and forcible assimilation.

Government employees began inventorying Native land and listing tribal members on Dawes Rolls in preparation for the allotments. Native leaders saw through the ruse and protested to Congress and through the courts. Not only would the act destroy any vestiges of traditional tribal self-government, but also communal ideas of land ownership and familial inheritance. Not dissuaded in the least, Congress passed the law in 1887,allotting each Native family 160 acres of land. Not only were the Five Southeastern Tribes in Oklahoma affected, so were other Natives in Oklahoma and Kansas, and throughout the West. The Curtis Act extended specifically to the Five Tribes of the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Cherokee, Creek/Muscogee and Seminole, through similar provisions. They would lose a combined 90 million acres in Oklahoma alone.

Chaos ensued. After the Natives had received their allotment of land, vast swaths of former reservation land were open for settlement. The government offered this land on the cheap to homesteaders who could prove it up. In Oklahoma, tribes had often had problems with White squatters known as Boomers, people who trespassed and set up farms on Native land and had to be forcibly removed by the Army. As rumors of impending land sales picked up, Sooners, or people who moved into Oklahoma sooner than the announced sale date were also a nuisance. Oklahoma experienced several land rushes, where Settlers would wait at the border of land intended for sale and rushed to claim the choicest parcels. The most famous was the Land Run of 1889, giving rise to the term 89'er, for people who had claimed land at that time, mostly land belonging to the Five Tribes. Another land run in 1891 opened Iowa, Sac and Fox, Potawatomi and Shawnee land. In 1892, Cheyenne and Arapahoe land was for sale. Then in 1893, land in the Cherokee Strip area of Oklahoma was sold. Then in 1895, Kickapoo land went the same way.

As White homesteaders rushed into the vacated lands, they ran into Sooners and Boomers who had settled their first and weren't about to go easily. Unscrupulous speculators also entered the act, buying land from Natives who weren't intending to prove up or farm their land, and would rather live as they always had, with relatives on their land. Many Natives had become used to reservation rationing. Without the seed, implements or knowledge of farming, and no game to hunt, many families found 160 acres of farmland to be completely useless anyway. Tribes who practiced communal ownership, or had a formerly nomadic lifestyle were totally unprepared for life as homesteaders and farmers, though many tried their best including Geronimo of the Apache. By 1900, tribes had lost over 2/3 of their original land, all self-government, and much of their traditional leadership and methods of kinship and property inheritance. To make matters worse, Congress did not extend citizenship to Natives until 1924, legal rights such as voting, suing in court and other means of protecting their rights were non-existent.

The downward spiral continued, Natives who lived in Oklahoma were affected by the Dust Bowl of the 1920's and the Depression of the 1930's. The Roosevelt Administration passed the Indian Reorganization Act, known as the Wheeler-Howard Law of 1934. This Act ended allotment, allowed tribes to organize their own self-government, apply for federal recognition and receive rights to tribal land which could not be sold to non-tribal members. It would take some tribes years to complete the process of achieving federal recognition, something many groups are still trying to achieve.

Comments

Post a Comment