Natives versus Army: the First Battle of Adobe Walls, 1864

Rivers of ink have been spilled over the Battle of the Little Bighorn/Greasy Grass and what Custer failed to do to save himself and his men. Twelve years before, an experienced Indian Fighter showed how an outnumbered force of cavalry could protect themselves against a numerically superior force of skilled Plains warriors and live to tell the tale.

The Santa Fe Trail was the main artery linking trade and settlement between St. Louis, Missouri and Santa Fe, New Mexico. Part of the trail led through Comanche and Kiowa country and they were not happy. They were aware that the settlers were not only occupying their hunting and home ranges, but also slaughtering buffalo and other game animals that were their basic food supply. Commanche, Kiowa and Plains Apache warriors felt justified in raiding wagon trains and either killing settlers or taking them captive. American authorities viewed the Natives as hostile enemies to be eradicated or contained. In 1861, the United States tore itself apart in the Civil War. With the states fighting each other, Natives could hope for a respite. But Gen. James H. Carleton, Union commander of the Military District of New Mexico, wasn't about to give them one. He intended to show the tribes of the Southern Plains that American forces could still hold their own in the west.

The Santa Fe Trail was the main artery linking trade and settlement between St. Louis, Missouri and Santa Fe, New Mexico. Part of the trail led through Comanche and Kiowa country and they were not happy. They were aware that the settlers were not only occupying their hunting and home ranges, but also slaughtering buffalo and other game animals that were their basic food supply. Commanche, Kiowa and Plains Apache warriors felt justified in raiding wagon trains and either killing settlers or taking them captive. American authorities viewed the Natives as hostile enemies to be eradicated or contained. In 1861, the United States tore itself apart in the Civil War. With the states fighting each other, Natives could hope for a respite. But Gen. James H. Carleton, Union commander of the Military District of New Mexico, wasn't about to give them one. He intended to show the tribes of the Southern Plains that American forces could still hold their own in the west.

Carleton turned to an experienced Indian Fighter who'd proven himself in battles against several tribes, including the Blackfoot and Navajo. Christopher "Kit" Carson was born in Kentucky, and made his mark in the west as a Mountain Man and guide. He was as well-known to Natives as Custer would later be, as someone who showed no mercy to man, woman or child. Carson's record on Native relations is mixed. He began his career as an Indian Fighter with a personal grudge against Natives, particularly the Blackfeet. Later, Carson would marry an Arapahoe and then a Cheyenne woman and would agree to serve as Indian Agent for the Utes, and later the Jicarilla Apaches. His time with the Indians softened his attitude, but only by a few clicks. While he was willing to be firm but fair to Natives who were compliant to U.S. policy, his attitude toward "hostile" tribes was still as unrelenting as ever. In 1862, Carleton had sent Carson to Arizona to bring the Navajo to a reservation. By 1864, after months of scorched earth tactics, Carson had forced hundreds of Navajo onto the Long Walk from their homeland in Arizona to the Bosque Redondo reservation in New Mexico, a chapter that haunts Navajo people to this day.

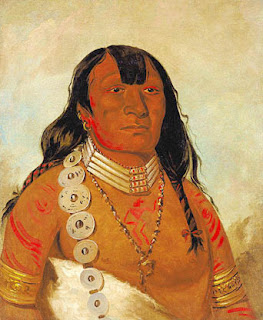

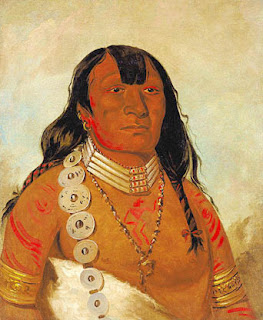

Carson recruited a force of 260 cavalry, 75 infantry, and 72 Ute and Jicarilla scouts and set out from Fort Bascom in New Mexico to what is now Hutchinson County, Texas. The Adobe Walls referred to were the ruins of one of William Bent's forts. Carson, a former employee and protégé of Bent, knew the area well. On November 24, 1864, his force reached Mule Springs, where the scouts picked up the trail of a large village. Carson left the infantry to guard the baggage and night-marched with is cavalry and the scouts to the old Bent fort. He intended to use the ruin as a potential base and hospital while he located and dealt with whatever Natives his scouts found. On November 25, 1864, his men raided a Kiowa village of 176 lodges. Principal Chief Dohasan quickly evacuated the women and children, and sent messengers to alert allied Comanche villages nearby. Guipago and Satanta prepared to fend off Carson's attack.

Dohasan's alarm brought Comanche and Kiowa Apache warriors to the scene, hundreds of them. Estimates very but the common estimate is 1200 to 1400 warriors. Carson had two pieces of artillery, which he used to deter the Native attack, but not for long. As more warriors came in, the Natives made repeated charges on horseback. And, unlike White cavalry, they knew how to use every inch of a galloping horse, sometimes leaning from the sides, or even under the horse's belly to aim arrows as fast as they could shoot. Dohasan, Satank, Satanta and Guipago led attack after attack and Carson knew he was outnumbered and running out of shot. Satanta got his hands on a bugle and complicated matters even more by mimicking the calls of Carson's buglers, further disorienting and demoralizing Carson's men. The Natives tried to block Carson's retreat by starting the prairie grass on fire. Not to be outdone, Carson started backfires and kept shooting.

He ordered his men to retreat to an empty Kiowa village, where they killed an elderly chief, Iron Shirt, who refused to evacuate. Carson's men set fire to the lodges, further adding to the confusion. He led his men to a bluff and continued to send howitzer shells into the charging warriors. Thus covering his retreat, he managed to return to his infantry at Mule Springs and regroup. The combined war party of Kiowa, Comanche and Plains Apache found a nearby bluff and awaited Carson's next move. Carson overruled his officers, who wanted to continue the attacks and decided on a retreat. The Native command team decided to let him leave without a fight. Casualties were 6 killed and 25 wounded for the Army, and 60 killed or wounded for the Natives. Since the battle, sources have claimed victory for both sides, but it was the Natives who remained in possession of the battlefield. While Carson's conduct saved his men's lives, it also signaled the end of Native dominance of the Southern Plains. Once the Civil War was over, more soldiers would come and there would be other battles to fight.

The Santa Fe Trail was the main artery linking trade and settlement between St. Louis, Missouri and Santa Fe, New Mexico. Part of the trail led through Comanche and Kiowa country and they were not happy. They were aware that the settlers were not only occupying their hunting and home ranges, but also slaughtering buffalo and other game animals that were their basic food supply. Commanche, Kiowa and Plains Apache warriors felt justified in raiding wagon trains and either killing settlers or taking them captive. American authorities viewed the Natives as hostile enemies to be eradicated or contained. In 1861, the United States tore itself apart in the Civil War. With the states fighting each other, Natives could hope for a respite. But Gen. James H. Carleton, Union commander of the Military District of New Mexico, wasn't about to give them one. He intended to show the tribes of the Southern Plains that American forces could still hold their own in the west.

The Santa Fe Trail was the main artery linking trade and settlement between St. Louis, Missouri and Santa Fe, New Mexico. Part of the trail led through Comanche and Kiowa country and they were not happy. They were aware that the settlers were not only occupying their hunting and home ranges, but also slaughtering buffalo and other game animals that were their basic food supply. Commanche, Kiowa and Plains Apache warriors felt justified in raiding wagon trains and either killing settlers or taking them captive. American authorities viewed the Natives as hostile enemies to be eradicated or contained. In 1861, the United States tore itself apart in the Civil War. With the states fighting each other, Natives could hope for a respite. But Gen. James H. Carleton, Union commander of the Military District of New Mexico, wasn't about to give them one. He intended to show the tribes of the Southern Plains that American forces could still hold their own in the west.Carleton turned to an experienced Indian Fighter who'd proven himself in battles against several tribes, including the Blackfoot and Navajo. Christopher "Kit" Carson was born in Kentucky, and made his mark in the west as a Mountain Man and guide. He was as well-known to Natives as Custer would later be, as someone who showed no mercy to man, woman or child. Carson's record on Native relations is mixed. He began his career as an Indian Fighter with a personal grudge against Natives, particularly the Blackfeet. Later, Carson would marry an Arapahoe and then a Cheyenne woman and would agree to serve as Indian Agent for the Utes, and later the Jicarilla Apaches. His time with the Indians softened his attitude, but only by a few clicks. While he was willing to be firm but fair to Natives who were compliant to U.S. policy, his attitude toward "hostile" tribes was still as unrelenting as ever. In 1862, Carleton had sent Carson to Arizona to bring the Navajo to a reservation. By 1864, after months of scorched earth tactics, Carson had forced hundreds of Navajo onto the Long Walk from their homeland in Arizona to the Bosque Redondo reservation in New Mexico, a chapter that haunts Navajo people to this day.

Carson recruited a force of 260 cavalry, 75 infantry, and 72 Ute and Jicarilla scouts and set out from Fort Bascom in New Mexico to what is now Hutchinson County, Texas. The Adobe Walls referred to were the ruins of one of William Bent's forts. Carson, a former employee and protégé of Bent, knew the area well. On November 24, 1864, his force reached Mule Springs, where the scouts picked up the trail of a large village. Carson left the infantry to guard the baggage and night-marched with is cavalry and the scouts to the old Bent fort. He intended to use the ruin as a potential base and hospital while he located and dealt with whatever Natives his scouts found. On November 25, 1864, his men raided a Kiowa village of 176 lodges. Principal Chief Dohasan quickly evacuated the women and children, and sent messengers to alert allied Comanche villages nearby. Guipago and Satanta prepared to fend off Carson's attack.

Dohasan's alarm brought Comanche and Kiowa Apache warriors to the scene, hundreds of them. Estimates very but the common estimate is 1200 to 1400 warriors. Carson had two pieces of artillery, which he used to deter the Native attack, but not for long. As more warriors came in, the Natives made repeated charges on horseback. And, unlike White cavalry, they knew how to use every inch of a galloping horse, sometimes leaning from the sides, or even under the horse's belly to aim arrows as fast as they could shoot. Dohasan, Satank, Satanta and Guipago led attack after attack and Carson knew he was outnumbered and running out of shot. Satanta got his hands on a bugle and complicated matters even more by mimicking the calls of Carson's buglers, further disorienting and demoralizing Carson's men. The Natives tried to block Carson's retreat by starting the prairie grass on fire. Not to be outdone, Carson started backfires and kept shooting.

He ordered his men to retreat to an empty Kiowa village, where they killed an elderly chief, Iron Shirt, who refused to evacuate. Carson's men set fire to the lodges, further adding to the confusion. He led his men to a bluff and continued to send howitzer shells into the charging warriors. Thus covering his retreat, he managed to return to his infantry at Mule Springs and regroup. The combined war party of Kiowa, Comanche and Plains Apache found a nearby bluff and awaited Carson's next move. Carson overruled his officers, who wanted to continue the attacks and decided on a retreat. The Native command team decided to let him leave without a fight. Casualties were 6 killed and 25 wounded for the Army, and 60 killed or wounded for the Natives. Since the battle, sources have claimed victory for both sides, but it was the Natives who remained in possession of the battlefield. While Carson's conduct saved his men's lives, it also signaled the end of Native dominance of the Southern Plains. Once the Civil War was over, more soldiers would come and there would be other battles to fight.

Comments

Post a Comment