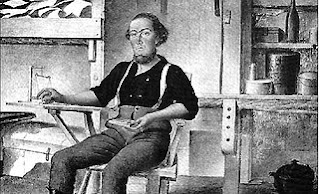

Chief of Scouts: Mitch Bouyer, 1837-1876

Mixed race people in the west bridged the gap between the Native and White worlds. Many of these people, known as Metis, were skilled interpreters and guides who provided access to trade, and served as go-betweens for both Natives and Whites. One of these talented men was Michel "Mitch" Bouyer, a mixed=race Lakota and French Canadian.

Mitch, 1837-1876, was the son of Jean-Baptiste Bouyer, a French-Canadian who worked for Astor's American Fur Company. He and his Santee Sioux wife had several children. Mitch had three sisters and at least two half-brothers. His father would be killed in 1863 while trapping in the wilderness. By 1869, Mitch had found work as an interpreter at Fort Phil Kearney. He married a Crow Woman named Magpie Outside, who sometimes went by the English name Mary. Their daughter, Mary, was born in 1869. They also had a son, Tom, who was taken in by a foster family after Mitch's death. Mitch was later employed by the 2nd U.S. Cavalry and worked for the Northern Pacific Railway. By 1872, he was employed at Crow Agency. Many military commanders respected him. Gen. John Gibbons called him the best scout next to Jim Bridger.

In the windup to Little Bighorn/Greasy Grass, Custer asked for Mitch to be transferred to the 7th Cavalry. Custer's regular Arikara scouts had been reassigned, so he would be working with Crow Scouts who were more familiar with the country. The scouts knew that many of the Natives opposing them considered them traitors and that they were all dead men. Mitch tried repeatedly to warn Custer about the sheer size of the Native encampment they were facing. He said, "General, I have been with these Indians for 30 years and this is the biggest village I have ever known of." Unconvinced, Custer pushed ahead. Mitch gave away his possessions, knowing he was going to die. He also smoothed matters over between Custer and the scouts, particularly Curley. The Crow were also aware they were going to die and chose to wear warrior's dress and not Army issue. Custer became incensed at what he perceived as cowardice and ordered the scouts to leave. Mitch saw no need for them to die unnecessarily and persuaded them all, including Curley to go away, thus saving their lives. Mitch was at Custer's side when he was killed.

In 1884, a fire burned over the battlefield site, enabling researchers to find a skull said to resemble Bouyer's face. At the time of the battle, he was dressed per usual, wearing a fur hat with two feathers and a piebald calfskin vest. His widow Mary was taken in by a friend, Thomas LeForge. After his wife's death, LeForge married her and raised Mitch's son Tom as his own.

Mitch, 1837-1876, was the son of Jean-Baptiste Bouyer, a French-Canadian who worked for Astor's American Fur Company. He and his Santee Sioux wife had several children. Mitch had three sisters and at least two half-brothers. His father would be killed in 1863 while trapping in the wilderness. By 1869, Mitch had found work as an interpreter at Fort Phil Kearney. He married a Crow Woman named Magpie Outside, who sometimes went by the English name Mary. Their daughter, Mary, was born in 1869. They also had a son, Tom, who was taken in by a foster family after Mitch's death. Mitch was later employed by the 2nd U.S. Cavalry and worked for the Northern Pacific Railway. By 1872, he was employed at Crow Agency. Many military commanders respected him. Gen. John Gibbons called him the best scout next to Jim Bridger.

In the windup to Little Bighorn/Greasy Grass, Custer asked for Mitch to be transferred to the 7th Cavalry. Custer's regular Arikara scouts had been reassigned, so he would be working with Crow Scouts who were more familiar with the country. The scouts knew that many of the Natives opposing them considered them traitors and that they were all dead men. Mitch tried repeatedly to warn Custer about the sheer size of the Native encampment they were facing. He said, "General, I have been with these Indians for 30 years and this is the biggest village I have ever known of." Unconvinced, Custer pushed ahead. Mitch gave away his possessions, knowing he was going to die. He also smoothed matters over between Custer and the scouts, particularly Curley. The Crow were also aware they were going to die and chose to wear warrior's dress and not Army issue. Custer became incensed at what he perceived as cowardice and ordered the scouts to leave. Mitch saw no need for them to die unnecessarily and persuaded them all, including Curley to go away, thus saving their lives. Mitch was at Custer's side when he was killed.

In 1884, a fire burned over the battlefield site, enabling researchers to find a skull said to resemble Bouyer's face. At the time of the battle, he was dressed per usual, wearing a fur hat with two feathers and a piebald calfskin vest. His widow Mary was taken in by a friend, Thomas LeForge. After his wife's death, LeForge married her and raised Mitch's son Tom as his own.

Comments

Post a Comment