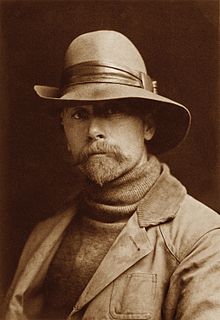

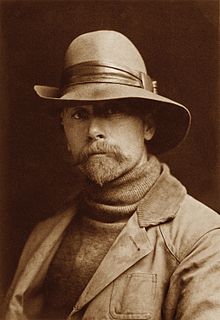

Photographer: Edward S. Curtis, 1868-1952

During the early years of the American frontier, painters such as Charles Bird King and George Catlin and ethnologists such as Thomas McKinney did much to preserve knowledge of Native tribes and cultures among White Americans. As the country expanded west and photography became practical, photographers also carried on this important work. What King and Catlin were to the painting world, Edward S. Curtis would become to the world of photography.

Curtis was born in Whitewater, Wisconsin in 1868. The family were farmers and struggled with constant poverty. When Curtis was still young, they moved to Minnesota, where Curtis' grandfather ran a grocery store. Edward Curtis remained in school until the 6th grade, but had to leave. Soon after, he built his own camera out of odds and ends. By the age of 17, he'd become apprenticed to a photographer in Minneapolis. By 1887, the family moved again, to Seattle, Washington. Curtis took a photograph of Chief Seattle's daughter, known as Princess Angeline. It would be his first photograph of a Native person. He soon began taking pictures of Natives in Washington, as well as the surrounding countryside. One day, while hiking Mt. Rainier, he gave directions to a lost group of hikers, one of whom, George Bird Grinnell, later invited Curtis to serve as official photographer of the Harriman Expedition to Alaska of 1899. Under Grinnell's patronage, Curtis joined an expedition to study and photograph people of the Blackfoot Confederacy in Motana, in 1900.

Curtis was born in Whitewater, Wisconsin in 1868. The family were farmers and struggled with constant poverty. When Curtis was still young, they moved to Minnesota, where Curtis' grandfather ran a grocery store. Edward Curtis remained in school until the 6th grade, but had to leave. Soon after, he built his own camera out of odds and ends. By the age of 17, he'd become apprenticed to a photographer in Minneapolis. By 1887, the family moved again, to Seattle, Washington. Curtis took a photograph of Chief Seattle's daughter, known as Princess Angeline. It would be his first photograph of a Native person. He soon began taking pictures of Natives in Washington, as well as the surrounding countryside. One day, while hiking Mt. Rainier, he gave directions to a lost group of hikers, one of whom, George Bird Grinnell, later invited Curtis to serve as official photographer of the Harriman Expedition to Alaska of 1899. Under Grinnell's patronage, Curtis joined an expedition to study and photograph people of the Blackfoot Confederacy in Motana, in 1900.

By 1906, Curtis work was beginning to attract more attention. Financier JP Morgan invested $75,000 to Curtis to produce a series of pictures books on Natives, entitled The North American Indian. The work grew to 20 volumes with over 1,500 pictures. In addition to photographing Natives, Curtis hired additional personnel to study the cultures of the people he was meeting and took extensive notes. Like Catlin before him, Curtis was concerned that Native culture would die out if it wasn't chronicled and preserved somehow. His commission to photograph the Natives grew into interviews with various individuals. It would be Curtis who would first ask Custer's surviving scouts, including Curley, exactly what happened at Little Bighorn. No one had though to ask them, or the victors of that battle, for their stories. Curtis also recorded on wax cylinders Native songs and stories, and wrote biographical sketches of leaders with whom he came into contact. His work would become the foundation for other studies of Native people.

Curtis had used primitive motion picture technology for the Morgan-funded study, but in 1912, engaged in a more ambitious motion picture essay of the Kwakiutl Tribe of Queen Charlotte Strait in British Columbia. His film, In the Land of the Head-Hunters, was the first feature-length documentary on Native people. Despite the acclaim he received for these ventures, Curtis received little in actual revenue. He eventually left for Hollywood, working as a cameraman for Cecille B. DeMille. Deeply, in debt, Curtis had to sell his rights to North American Indian and In the Land of the Head-Hunters. His prints and negatives would eventually find their way to Boston, where they lay undiscovered for decades. Today, several universities and museums have repositories of Curtis' work, including Northwestern University, the Library of Congress, the Lauriat Archive, Peabody Essex Archive, Indiana University and the University of Wyoming.

Curtis was born in Whitewater, Wisconsin in 1868. The family were farmers and struggled with constant poverty. When Curtis was still young, they moved to Minnesota, where Curtis' grandfather ran a grocery store. Edward Curtis remained in school until the 6th grade, but had to leave. Soon after, he built his own camera out of odds and ends. By the age of 17, he'd become apprenticed to a photographer in Minneapolis. By 1887, the family moved again, to Seattle, Washington. Curtis took a photograph of Chief Seattle's daughter, known as Princess Angeline. It would be his first photograph of a Native person. He soon began taking pictures of Natives in Washington, as well as the surrounding countryside. One day, while hiking Mt. Rainier, he gave directions to a lost group of hikers, one of whom, George Bird Grinnell, later invited Curtis to serve as official photographer of the Harriman Expedition to Alaska of 1899. Under Grinnell's patronage, Curtis joined an expedition to study and photograph people of the Blackfoot Confederacy in Motana, in 1900.

Curtis was born in Whitewater, Wisconsin in 1868. The family were farmers and struggled with constant poverty. When Curtis was still young, they moved to Minnesota, where Curtis' grandfather ran a grocery store. Edward Curtis remained in school until the 6th grade, but had to leave. Soon after, he built his own camera out of odds and ends. By the age of 17, he'd become apprenticed to a photographer in Minneapolis. By 1887, the family moved again, to Seattle, Washington. Curtis took a photograph of Chief Seattle's daughter, known as Princess Angeline. It would be his first photograph of a Native person. He soon began taking pictures of Natives in Washington, as well as the surrounding countryside. One day, while hiking Mt. Rainier, he gave directions to a lost group of hikers, one of whom, George Bird Grinnell, later invited Curtis to serve as official photographer of the Harriman Expedition to Alaska of 1899. Under Grinnell's patronage, Curtis joined an expedition to study and photograph people of the Blackfoot Confederacy in Motana, in 1900.By 1906, Curtis work was beginning to attract more attention. Financier JP Morgan invested $75,000 to Curtis to produce a series of pictures books on Natives, entitled The North American Indian. The work grew to 20 volumes with over 1,500 pictures. In addition to photographing Natives, Curtis hired additional personnel to study the cultures of the people he was meeting and took extensive notes. Like Catlin before him, Curtis was concerned that Native culture would die out if it wasn't chronicled and preserved somehow. His commission to photograph the Natives grew into interviews with various individuals. It would be Curtis who would first ask Custer's surviving scouts, including Curley, exactly what happened at Little Bighorn. No one had though to ask them, or the victors of that battle, for their stories. Curtis also recorded on wax cylinders Native songs and stories, and wrote biographical sketches of leaders with whom he came into contact. His work would become the foundation for other studies of Native people.

Curtis had used primitive motion picture technology for the Morgan-funded study, but in 1912, engaged in a more ambitious motion picture essay of the Kwakiutl Tribe of Queen Charlotte Strait in British Columbia. His film, In the Land of the Head-Hunters, was the first feature-length documentary on Native people. Despite the acclaim he received for these ventures, Curtis received little in actual revenue. He eventually left for Hollywood, working as a cameraman for Cecille B. DeMille. Deeply, in debt, Curtis had to sell his rights to North American Indian and In the Land of the Head-Hunters. His prints and negatives would eventually find their way to Boston, where they lay undiscovered for decades. Today, several universities and museums have repositories of Curtis' work, including Northwestern University, the Library of Congress, the Lauriat Archive, Peabody Essex Archive, Indiana University and the University of Wyoming.

Comments

Post a Comment